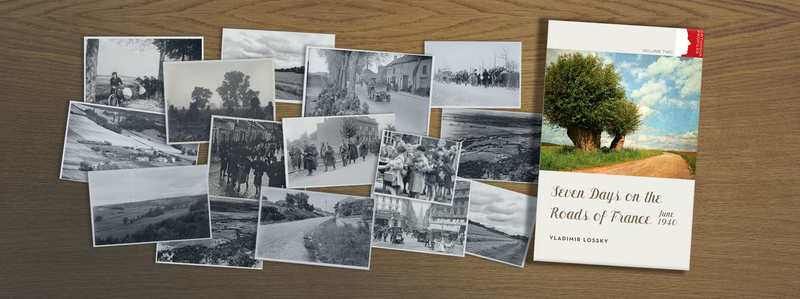

Review: Seven Days on the Roads of France

Posted by SVS Press on 6th Aug 2020

Anyone who wants to know more about Vladimir Lossky, the man behind several grand theological works, must not miss out on the sheer pleasure of reading Seven Days on the Roads of France, published by St Vladimir’s Seminary Press (SVS Press). Lossky’s moving and lyrical diary tells the story of his journey, on foot, through the heart of World War II France as the German army closes in on Paris.

Lossky, known primarily for his masterwork, The Mystical Theology of the Eastern Church (also available from SVS Press), was a member of the Russian émigré generation that settled in France after fleeing the Soviet Union. He was considered the foremost theologian of that generation and was key to the patristic renewal in twentieth-century Orthodox theology.

In Seven Days on the Roads of France, Lossky tries to join the French Army but is sent from one gendarmerie to another. Along the way, he has memorable and poignant encounters with villagers, townspeople, and fellow refugees, all terrified at the invasion and exhausted from the ordeal:

I went into a large farmyard, where a reception centre had been set up in the barns. The straw was dirty, as were the people who slept beside me. But a fraternity of misery, of the sort born at the lowest point of common degradation, brought us together. We forgot everything, save the very human feeling of solidarity in misfortune. It was on the roads of France that I got to know this feeling. Never shall I forget it.

As he journeys further and further south, writes translator Michael Donley, Lossky “has time to reflect upon the meaning of suffering and on matters that have become uncannily topical again in our own day. These include the true nature of Christian or western civilization (indeed of Christianity itself); the rightness or otherwise of war against enemy attacks on it; the problems of any relationship between Church and State; what we mean—or should mean—by ‘Europe’ or any ‘nation’; secularization; the problems posed by the mass movements of peoples.”

Lossky also reflects on his warm love for France and on her “spiritual destiny,” which, writes Donely, Lossky understood to be “‘a focus of regeneration for Western Christianity in a Europe that [was] already becoming de-Christianized.’” One would think that such a celebrated Orthodox theologian might be an Orthodox triumphalist but, far from it, Lossky acknowledges France’s martyrs and saints who sanctified both the land and French culture—the supreme archetype being Joan of Arc:

The purpose of Joan of Arc’s divine mission, for example, was itself relative: to lead the Dauphin to Rheims in order to give France back her king. She felt no animosity towards the English soldiers whom it was her duty to drive out of France. This is one of the main features of the ‘human’ warfare that she waged. It is also a distinctive characteristic of the soul of France herself, of whom Joan is the most perfect image.

This is a wonderfully written work, and Lossky has a keen eye for humor and absurdity. In this encounter in an empty cathedral in the town of Orleans, he witnesses an elderly Frenchman seemingly out of his mind:

A tall old man with a stoop, wearing an old fashioned fin-de-siecle frock coat, was waving his arms about, threatening and cursing someone. He had a fine face, the look of a well-bred provincial gentleman, a devout and God-fearing type. I drew nearer, to see who he was so angry with. He was going round the cathedral, stopping before each statue of a saint. It was to them that he was addressing his curses, his cries, his threats. “Alors, quoi? Damn it all, then! Don’t you want to help us? Can’t you help us?” . . . I left the cathedral, quite overcome. You really needed to have a faith that was deep and sincere, a genuine inner freedom before God and His saints, to be able to talk to them like that. No, he wasn’t a madman. Rather, a noble Christian soul, seized with despair and bitterness, pouring out his pain to the saints, who remained motionless and silent, guides of the divine ways that are so painful for us to follow.

Along with Lossky’s diary, this edition includes four epilogues written by Lossky’s children, offering further illumination into his remarkable character. This edition marks the first time that this diary appears in English. A debt of gratitude is owed to Donley for allowing English readers a chance to know the man behind the theology.